Any baseball franchise would want to employ a powerful first

baseman with a career OPS (On-base Plus Slugging) over 1.000 who could

also play the outfield.

Clubs would also welcome a hard-nosed second baseman who had won a Rookie-of-the-Year Award, an MVP, and a batting title.

Teams would be thrilled to add a smooth center fielder worth nearly 80 career WAR (Wins Above Replacement).

They’d be even more interested if you told them each player was a Hall-of-Famer and had served his country as a soldier in time of actual war.

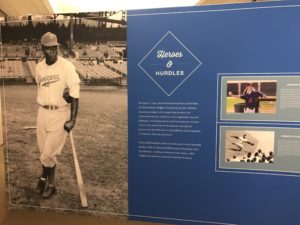

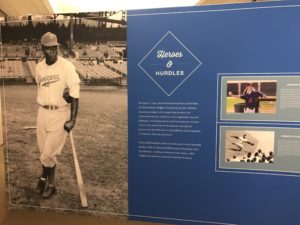

I learned things about each of the above players at a new exhibit called Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American. The Congregation Ahavath Sholom on South Hulen hosts it through March 5. You can get more scoop on its contents and how it came to be in Fort Worth by reading my article in the Fort Worth Weekly print edition due on stands this coming Wednesday.

It seemed especially appropriate to write about the exhibit as we celebrate Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. King chased dreams, and, indeed we remember one of his most famous speeches as the “I Have A Dream Speech.” He delivered it August 28, 1963 in Washington, D.C., and it contains one of my favorite passages ever:

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

King’s address also spoke of the injustices done to African-Americans of the time and of difficulties they faced in a country whose laws denied them a level playing field. The exhibit talks of the discriminatory obstacles Jewish ballplayers faced, and includes mentions of the struggles and triumphs of black, Hispanic, and even female ballplayers.

We learn, for instance, that while early Jewish ballplayers could at least play in the big leagues (unlike African-Americans), many felt compelled to change their names to something that made their ethnicity less apparent. We also learn that baseball played a role in helping to overcome prejudices, both within the game and without.

“Baseball really became the place for cultural change in America, with Jackie Robinson as the place where America really began its integration,” posited event organizer Rick Hollander.

Robinson was the second baseman I described in this column’s opening paragraph. His status as MLB’s first African-American player in the modern era has deservedly cemented his status as a legend, and Robinson’s performance on the baseball diamond would have earned any player Hall of Fame consideration.

Rick Weintraub, a lifelong baseball fan who attended the exhibit the day I was there told us he had once gotten to meet Jackie Robinson. The nearly 80-year old white Jewish man said, “It now just almost brings tears to my eyes because he was such a great man, much less a baseball player.”

As one of the first Jewish ballplayers to keep his traditional surname, the first baseman/outfielder described above also faced racially-tinged abuse. Detroit Tigers fans, however, liked Hank Greenberg’s two MVP seasons and pair of World Series wins.

Both Greenberg and Robinson used their play on the field and their strength off it to power through much of the flimsy excuse for a mindset that is racism. They left baseball observers with little choice other than to judge them by the contents of their characters. I would submit that such developments have value in the wider world. Once one realizes that a member of a maligned group defies negative stereotypes, it makes it more difficult to project suppositions of inferiority onto other individuals.

Open competition, and sports especially, rewards such rational choices. Fans of that era discovered they would rather brag about their teams winning than obsess over whether the players looked like them or attended their church.

Speaking of winning, there’s another important day on the national calendar this week. Another prominent citizen will have a chance to address the public from the capital. Friday is Inauguration Day, and the incoming POTUS has talked a lot about winning things.

One thing the exhibits explains is how first-generation Americans used baseball to successfully bridge cultural gaps.

“Regardless of what all the politicians say in the world today, we are an immigrant society,” said Hollander. “They came here as young as eight, nine years old. They went back and fought in World War II for their new country and the patriotism was real. They understood the opportunities that America had to offer and baseball was one of those opportunities.”

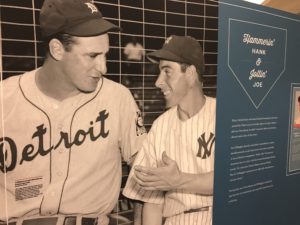

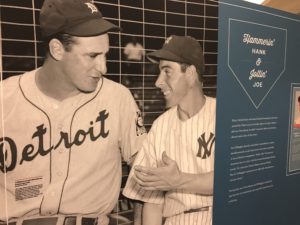

All three of the men mentioned at the top of the page also served in the armed forces during WWII. One of the exhibition’s panels features a photo of Greenberg with the center fielder I cited. Joe DiMaggio might have been the most revered ballplayer in the world in 1941 and would join the Army from 1943-45. But when war broke out, the authorities wouldn’t allow his Sicilian father to earn a living fishing in San Francisco’s coastal waters because of where Giuseppe DiMaggio was born.

The Franklin D. Roosevelt administration judged a lot of Italians, Japanese, and others of Axis descent by something other than the content of each person’s character. The year after the U.S. government freed the last of the interned Japanese Americans, Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. As Hollander pointed out to me, the Major Leagues now feature players from all over, including Central and South America, the Caribbean, Korea, Australia, and, yes, Japan.

Society has made progress, too, since the 1940s. A more open world has resulted in all manner of free exchange of goods, services, music, and food. Indeed, as I walked into the synagogue to view the Chasing Dreams exhibit, a flier on the door caught my eye. This Jewish religious institution was advertising a musical Shabbat featuring the sounds of Latin America.

We’d like it if everyone kept an open mind about such cross-cultural experiences. When you adopt such an attitude, you can look at someone new or different as an individual and judge him or her accordingly.

If one views a person negatively because she shares a country of origin or a religion with billions of peaceful people and a tiny percentage of Bin Ladens, Torequmadas, Castros, or Maos; if one thinks just because a man rises to head a corporation or hedge fund, he therefore has no soul; if one believes that just because someone proved him or herself popular in an election, it automatically makes the official worthy or respect – or derision; In all these cases, one is not rendering judgement based on the content of that person’s character.

Baseball learned long ago how thinking that way prevents you from winning. The teams that employed Robinson, Greenberg, and DiMaggio won a LOT. One hopes that those taking power remember the lessons baseball – and Dr. King’s speech – have taught.

Clubs would also welcome a hard-nosed second baseman who had won a Rookie-of-the-Year Award, an MVP, and a batting title.

Teams would be thrilled to add a smooth center fielder worth nearly 80 career WAR (Wins Above Replacement).

They’d be even more interested if you told them each player was a Hall-of-Famer and had served his country as a soldier in time of actual war.

I learned things about each of the above players at a new exhibit called Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American. The Congregation Ahavath Sholom on South Hulen hosts it through March 5. You can get more scoop on its contents and how it came to be in Fort Worth by reading my article in the Fort Worth Weekly print edition due on stands this coming Wednesday.

It seemed especially appropriate to write about the exhibit as we celebrate Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. King chased dreams, and, indeed we remember one of his most famous speeches as the “I Have A Dream Speech.” He delivered it August 28, 1963 in Washington, D.C., and it contains one of my favorite passages ever:

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

King’s address also spoke of the injustices done to African-Americans of the time and of difficulties they faced in a country whose laws denied them a level playing field. The exhibit talks of the discriminatory obstacles Jewish ballplayers faced, and includes mentions of the struggles and triumphs of black, Hispanic, and even female ballplayers.

We learn, for instance, that while early Jewish ballplayers could at least play in the big leagues (unlike African-Americans), many felt compelled to change their names to something that made their ethnicity less apparent. We also learn that baseball played a role in helping to overcome prejudices, both within the game and without.

“Baseball really became the place for cultural change in America, with Jackie Robinson as the place where America really began its integration,” posited event organizer Rick Hollander.

Robinson was the second baseman I described in this column’s opening paragraph. His status as MLB’s first African-American player in the modern era has deservedly cemented his status as a legend, and Robinson’s performance on the baseball diamond would have earned any player Hall of Fame consideration.

Rick Weintraub, a lifelong baseball fan who attended the exhibit the day I was there told us he had once gotten to meet Jackie Robinson. The nearly 80-year old white Jewish man said, “It now just almost brings tears to my eyes because he was such a great man, much less a baseball player.”

As one of the first Jewish ballplayers to keep his traditional surname, the first baseman/outfielder described above also faced racially-tinged abuse. Detroit Tigers fans, however, liked Hank Greenberg’s two MVP seasons and pair of World Series wins.

Both Greenberg and Robinson used their play on the field and their strength off it to power through much of the flimsy excuse for a mindset that is racism. They left baseball observers with little choice other than to judge them by the contents of their characters. I would submit that such developments have value in the wider world. Once one realizes that a member of a maligned group defies negative stereotypes, it makes it more difficult to project suppositions of inferiority onto other individuals.

Open competition, and sports especially, rewards such rational choices. Fans of that era discovered they would rather brag about their teams winning than obsess over whether the players looked like them or attended their church.

Speaking of winning, there’s another important day on the national calendar this week. Another prominent citizen will have a chance to address the public from the capital. Friday is Inauguration Day, and the incoming POTUS has talked a lot about winning things.

One thing the exhibits explains is how first-generation Americans used baseball to successfully bridge cultural gaps.

“Regardless of what all the politicians say in the world today, we are an immigrant society,” said Hollander. “They came here as young as eight, nine years old. They went back and fought in World War II for their new country and the patriotism was real. They understood the opportunities that America had to offer and baseball was one of those opportunities.”

All three of the men mentioned at the top of the page also served in the armed forces during WWII. One of the exhibition’s panels features a photo of Greenberg with the center fielder I cited. Joe DiMaggio might have been the most revered ballplayer in the world in 1941 and would join the Army from 1943-45. But when war broke out, the authorities wouldn’t allow his Sicilian father to earn a living fishing in San Francisco’s coastal waters because of where Giuseppe DiMaggio was born.

The Franklin D. Roosevelt administration judged a lot of Italians, Japanese, and others of Axis descent by something other than the content of each person’s character. The year after the U.S. government freed the last of the interned Japanese Americans, Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. As Hollander pointed out to me, the Major Leagues now feature players from all over, including Central and South America, the Caribbean, Korea, Australia, and, yes, Japan.

Society has made progress, too, since the 1940s. A more open world has resulted in all manner of free exchange of goods, services, music, and food. Indeed, as I walked into the synagogue to view the Chasing Dreams exhibit, a flier on the door caught my eye. This Jewish religious institution was advertising a musical Shabbat featuring the sounds of Latin America.

We’d like it if everyone kept an open mind about such cross-cultural experiences. When you adopt such an attitude, you can look at someone new or different as an individual and judge him or her accordingly.

If one views a person negatively because she shares a country of origin or a religion with billions of peaceful people and a tiny percentage of Bin Ladens, Torequmadas, Castros, or Maos; if one thinks just because a man rises to head a corporation or hedge fund, he therefore has no soul; if one believes that just because someone proved him or herself popular in an election, it automatically makes the official worthy or respect – or derision; In all these cases, one is not rendering judgement based on the content of that person’s character.

Baseball learned long ago how thinking that way prevents you from winning. The teams that employed Robinson, Greenberg, and DiMaggio won a LOT. One hopes that those taking power remember the lessons baseball – and Dr. King’s speech – have taught.

No comments:

Post a Comment